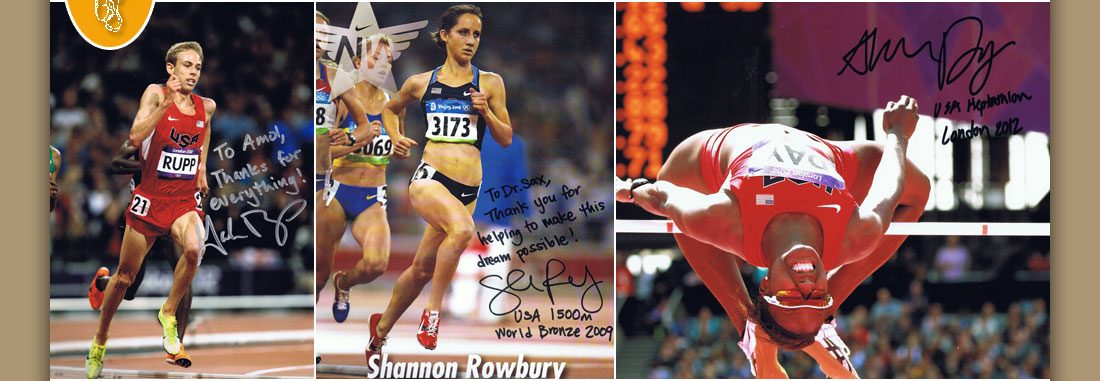

Dr. Amol Saxena, DPM

Palo Alto Foundation

Medical Group

Dept. of Sports Medicine

3rd Floor, Clark Building

795 El Camino Real

Palo Alto, CA 94301

Office: 650-853-2943

Fax: 650-853-6094

E-Mail

Map | Directions

| Articles |

Trauma to Lisfranc's Joint -- An Algorithmic Approach. The Lower Extremity.

Address Correspondence to:

Amol Saxena, DPM FACFAS, FACFAOM

Department of Sports Medicine,

Palo Alto Medical Foundation

300 Homer Avenue

Palo Alto, CA 94301

Phone: (650) 853-2943

Fax: (650) 853-6094

ABSTRACT

40 Lisfranc's injuries were retrospectively reviewed from 1992-1996. Injuries were classified into sprains (18), acute fracture/dislocations (4), post-traumatic degenerative joint disease (11), and fusions (7). There were 28 females and 12 males, average age 36.2 years old. Patients were evaluated for their ability to return to activities and function. The AOFAS Midfoot rating scale was used for fusion patients, yielding an average score of 86.4/100, and 71% good to excellent results. Sprains took an average of 3.5 months to return to activities (ranging from 1 month in Grade I injury to 6 months with some Grade III injuries). Fracture/dislocations took 4.75 months to return to activity, with no additional degenerative changes developing on follow-up (average 24 months). Patients who presented with post-traumatic pain often were under-treated initially, and due to continued symptoms were generally unable to maintain their desired activity level. An algorithm was created retrospectively to aid in treating future patients. Similar results were obtained to other studies on trauma to Lisfranc's Joint.

Key Words: Lisfranc's Joint, Tarso-Metatarso Sprain, Tarso-Metatarso Fracture/dislocation, Midfoot Sprain, Midfoot Fusion

INTRODUCTION

Trauma to the Tarso-Metatarsal Joint was first identified during the Napoleonic Wars, by Lisfranc, a war surgeon. Since then many authors have sought to classify and outline treatment for these injuries.(1-4) Literature is replete with descriptions on treatment for fractures and dislocations, however, there is a paucity of material on care for sprains and post-traumatic sequelae.(5) Relatively few papers with adequate long term follow-up are present for the results of surgical fusions. (6, 7) Though mostly anecdotal, primary fusion for severe fracture dislocations, especially those involving intra-articular injuries has been mentioned.(4,8,9)

Evaluation of these injuries has been difficult. Myerson indicates that "the true extent of the injury is often not appreciated and the more subtle forms of this injury are misdiagnosed."(8) Recent literature indicates weight-bearing or stress radiographs under fluoroscopy radiographs as needed to assess soft tissue integrity, particularly the first intra-osseous tarso-metatarso (Lisfranc’s) ligament: this spans from the medial cuneiform to the second metatarsal base. Injury to this articulation results in widening known as "Diastasis". Widening of more than 4 mm of the first and second rays indicates rupture of Lisfranc's Ligament, (or more than 2 mm than the contralateral limb). Most authors now recommend open surgical reduction if this injury is present. (5, 6, 8)

Technicium Bones Scans may also reveal "hidden" pathology, however they are often reserved for late evaluation of these injuries, particularly for arthrosis. Computerized Axial Tomography (CAT) Scans are also useful in identifying occult fractures and dislocations. Though imaging modalities are helpful at arriving at the diagnosis, appropriate treatment, specifically the length of treatment as only recently been detailed, particularly for soft tissue injury and post-traumatic sequelae.(5, 8) Myerson indicates the prevalence of post-traumatic arthritis ranges from 0-50 percent according to literature.(8) Sangeorzan et al reveal that even anatomical reduction can still result in post-traumatic arthritis, necessitating fusion.(6)

The purpose of this paper is to reveal the treatment regimens that allow patients with trauma to Lisfranc's joint to return to function and indicate approximate time frames. Various types of injuries will be assessed. Subsequently an algorithm for suggested treatment of acute and chronic injuries to the Tarso-Metatarso articulation will be presented so that the reader may hopefully achieve the same results and outcomes as this and other authors have achieved.

MATERIALS & METHODS

Patients treated by the author and available for follow-up were included in the study. Patients had their injury diagnosed and treated from 1992 to 1996. Injuries evaluated were to Lisfranc's Joint (tarso-metatarso articulation); additional concomitant injuries elsewhere may have occurred. Injuries where classified as "sprains", in which there was absence of bony and ligamentous disruption/dislocation. The "sprains" were further classified into Grade I, II and III sprains.

The second category of classification was acute fracture/dislocation; these patients were generally seen within 72 hours of injury. These injuries included avulsion fractures and/or displacement of the bones comprising Lisfranc’s joint. Due to the number of patients presenting with chronic pain a third category was created. "Post-Traumatic DJD" included patients who had prior injury to Lisfranc's Joint and now exhibited pain and loss of function, along with degenerative findings upon radiographic examination. The fourth category was patients who underwent fusion to Lisfranc's joint, due to recent trauma (severe fracture/dislocation) or "post-traumatic DJD".

The final end-point was how the patients were categorized, e.g. a patient with post-traumatic DJD who underwent a fusion was classified as a "fusion". Patients with Charcot's/Neuropathic Arthropathy were excluded from this study, due to their own unique difference and complications associated with this condition.

All patients were evaluated for return to function and activity, and specifically for the length of time it took to achieve such. Patients undergoing fusion were evaluated by the AOFAS Midfoot Scale. An Algorithm was constructed based on these patients’ treatment and resultant outcomes to guide in future treatment.

RESULTS

Forty patients were available for inclusion in the study, 28 females and 12 males, average age 36.2 years. Eighteen patients sustained Lisfranc's Sprains. Grade I sprains were treated with an arch support, ice and limitation of activity for approximately one month. Grade II and III sprains were treated with non-weight bearing below-the-knee cast boots for two to six weeks and additional protected weight-bearing in removable cast boots for two to six weeks depending on the severity. (See Tables 1 and 2) They returned to normal activity on average in 3.5 months, (range one to six months). Four patients with Lisfranc's fracture/dislocations took on average 4.75 months to return to full activity. None of these four patients had surgical reduction due to minimal (<2 mm) displacement; they were treated with four weeks non-weight bearing in a below-the-knee cast boot and four weeks weight-bearing removable cast boot. Patients with Post-Traumatic DJD rarely were able to return to regular desired activities. These 11 patients reduced their activity level and used foot orthoses; three are contemplating fusion due to continued pain.

Seven patients had a total of 25 joints fused due to Lisfranc's Trauma. (Only one patient necessitated all five Tarso-Metatarsal joints fused.) Two of these patients had acute fracture dislocations. In general, the techniques of Sangeorzan and Hansen were followed.(6) The average AOFAS Midfoot Rating Scale was 86.4/100; average follow-up was 24 months. Five out of the seven were able to get back to their usual activities in six months and had good to excellent results; their average age was 60.2 years. Two of the seven fusion patients that were rated as "poor" results had delayed diagnoses. Open Reduction and Internal Fixation was attempted first due to their young age (28 and 36 years), but still have continued pain, possibly necessitating additional fusions. (See Table 3)

DISCUSSION

Evaluating the Lisfranc's Trauma patient necessitates a high index of suspicion for any injury to the foot in which the forefoot is fixed or strapped, and then twisted. This is common with foot bindings (e.g. windsurfing, snow boarding). Also, dancing and soccer were common sports involved with this injury. The patient's activity at the time of injury will be helpful in arriving at the diagnosis. Common presenting misdiagnoses include dorsal exostoses, metatarsalgia, turf-toe, stress fracture and even Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy. The most significant portion of this injury that is overlooked is diastasis between the first and second rays, which often leads to continued subluxation and eventually arthrosis. Many authors cite the need to assess diastasis with "stress" or weight bearing x-rays, but do not indicate how soon these should be done. This author prefers to apply a compression dressing with a posterior splint, and keep the patient non-weight bearing until edema and pain is reduced enough to allow for full weight bearing AP and Lateral views. As cited by other authors, widening more than 4 mm between the first and second rays or, Metatarsal to Tarsal incongruence of more than 2 mm, is the indication for ORIF.(4, 5, 6, 8) Some authors recommend primary fusion with even pure ligamentous injury, due to the likelihood of additional subluxation and arthrosis; they feel fusion is inevitable.(4,10) Myerson advocates stress views under anesthesia utilizing fluoroscopy to be the most reliable to assess instability, but does not indicated how close to the time of injury or attempted reduction this is done.(8)

The results from the study presented here are similar to other authors. Essentially all of the patients in this study, particularly those in the "sprain" and "fracture/dislocation" categories were "athletic". Curtis et al reviewed 19 tarsometatarsal injuries in athletes. Sixteen of their patients were able to return to their pre-injury activity level in an average of 4.1 months - three were unable. Even with minor "sprains", seven patients in their study took 3 months to return, and two were unable. Five patients had "ORIF" done acutely with a 3.5 Cortical Screw obliquely placed to reduce the diastasis, kept non-weight bearing for 10-12 weeks, with screw removal done at 12-16 weeks.(5) Myerson feels that 4th and 5th Metatarso-cuboid fusion is rarely indicated, and does not find bone scans useful in identifying which joints to fuse. He found stress views under fluoroscopy more useful in identifying diastasis.(8)

Sangeorzan et al reviewed their series of Tarso-Metatarsal fusions. They had 16 patients over nine years available for follow-up, with patient's average age of 38 years. Good to excellent results were obtained in 11 patients (69%); five patients were rated as fair to poor. They concluded that injuries that had a long delay in treatment had a significant negative correlation to good outcome. In addition, those injuries that occurred on the job were less likely to have a good outcome. The surgical results of their technique seems to be acceptable to the orthopedic community and is often cited as the benchmark. They acknowledge a 69% success rate may not be acceptable for elective surgery, but realistic for revision/salvage surgery.(6) (Table 5)

The main findings of this paper are the length of time it takes to recover from injuries to

Lisfranc's joint, once they are appropriately treated. Unlike other sprains to the lower extremity, particularly the lateral ankle, these take on average 3.5 months to heal. The author has found surgical patients for other types of pathology can return to activities sooner, than those with just a "sprain" to Lisfranc's articulation. Furthermore, athletic patients, and now insurance carriers like to quantify "down-time". The results from this study and others must be stressed to all parties alike: patients, health care providers, and insurance carriers.

Another interesting point that is often cited with trauma to Lisfranc's joint is subsequent arthrosis. Though fusion of the lateral two rays is generally not needed, three patients in this series had post-traumatic DJD of the third and fourth Tarso-metatarso articulations; one would wonder about surgical fusion of this region.(6,8) Myerson indicates that despite anatomical reduction, arthritis may develop.(8) None of the patients suffering fracture/dislocations who were treated acutely by the author, showed symptoms of arthrosis two years post injury. Conversely, many patients who presented with post-traumatic arthrosis, had often vague recollection of trauma, minimal initial treatment, yet subsequently had significant symptoms, compromising daily functions. Compatible with Myerson and Sangeorzan’s findings, the two poor results with fusion, had delays in diagnoses of 3 months and one year, respectively. (6,8)

Fusions to Lisfranc's joint has been thought of as a progressive procedure, namely, arthrosis of adjacent joints progresses after initial arthrodesis occurs. Many authors have not found that to be true.(6, 8) This author along with others feel, post-arthrodesis pain may be due to incomplete and/or breakdown of fusion sites. The author has experienced this with both autogenous iliac crest bone and coral bone graft substitute; assessing fusion breakdown is difficult. Technicium bone scan will often still be "positive". CAT Scans often do not give adequate information about fusion status of medullary bones, such as in the midfoot, and metal fixatives obscure signal. The author has found Tomograms to be the most reliable. A separate paper dealing with the specifics of fusion will be forthcoming.

CONCLUSION

Treatment of Lisfranc's injuries can be confusing and complex. Often a minor "sprain" may entail a protracted course of healing, straining the doctor-patient relationship. Doctors and patients, both, often under-estimate the severity and length of disability from these injuries. Sprains to this region take more than three months for recovery. The results from this large series of podiatric cases and other orthopedic studies indicate earlier diagnosis and subsequently, appropriate treatment has better functional outcome. Fusion if needed, has approximately 70% good to excellent outcome. Early diagnosis is associated with better outcome.

Table 1 - Lisfranc’s Injuries (1992-96)

Sprains (Grade I-III) = 18

Fracture/Dislocations = 4

Post Trauma DJD = 11

Fusions = 7

28 Females, 12 Males, Average Age = 36.2

Table 2 - Return to Activities/Function

Sprains Avereage = 3.5 months, Range = 1-6 months

2 patients with delayed diagnosis > 1 year not included

Fracture/Dislocations: Average = 4.75 months, Avereage/fikki up 24 months

Table 3 - Results of Fusions (Ave F/U 24 Mos): 25 Jts Fused

Return to Activities:5/7 Average = 6 months (Average Age 60.2 years),

2/7 continued pain additional treatment (Average Age 32 years)

AOFAS Midfoot Rating Scale = 86.4/100 (100, 100, 98, 92, 85, 65, 65)

Note "65’s" had delay in diagnosis 3 &12 months; ORIF attempted first.

Table 4 - Other Author’s Results:

Curtis, Myerson & Szura: ‘93 Am J. of Sports Med., Vol 21, No. 4 "Tarsometatarsal Jt. Injuries in the Athlete"

19 Injuries; 16 returned to activities 4.1 months; 3 unable

9 "minor sprains", 7 took 3 mos to return to activities, 2 unable.

5 pts had ORIF w. 3.5 mm cortical screw obliquely, NWB x 10-12 wks; screw removed @ 12-16 wks.

Table 5 - Other Author’s Results:

Sangeorzan, Veith, & Hansen: ‘90 Foot & Ankle, Vol. 10, No. 4 "Salvage of Lisfranc’s Tarsometatarsal Jt. By Arthrodesis"

16 pts over 9 yrs, 49 Jts Fused, average age 38 yrs.

Good to Excellent results: 11 pts. (69%)

Fair to Poor: 5 pts.

Injuries that incurred a long delay in treatment showed a significant negative correlation to outcome.

References

1. Bohler L. The Treatment of Fractures 5th Edition, Vol 3, Grune & Stratton, New York, 1958.

2. Quenu E., Kuss G. Etude sur les luxations du metatose. Rev. Chir. 39:231-336, 730-791, 1093-1094, 1909.

3. Aitken AP, Poulson D. Dislocations of the tarso-metatarsal joint. J. Bone Joint Surg. 45A:246-260, 1963.

4. Hardcastle PH, Reschauer R, Hutscha-Lissberg E. Injuries to the tarso-metatarsal joint: incidence, classification and treatment. J. Bone Joint Surg. 64B:349-356, 1982.

5. Curtis M, Myerson M, Szura B. Tarso-metatarsal joint injuries in the athlete. Am. J. Sports Med. Vol 21 (4):497-502, 1993.

6. Sangeorzan B, Veith R, Hansen S. Salvage of Lisfranc’s tarso-metatarsal joint by arthrodesis. Foot & Ankle Vol 10 (4):193-200, 1990.

7. Johnson S, Johnson K. Dowel arthrodesis for degenerative arthrodesis of the tarso-metatarsal (Lisfranc) joints. Foot & Ankle 5:243-253, 1986.

8. Myerson M. Tarso-metatarsal arthrodesis: Technique and results of treatment after injury. in Foot Ankle Clinics. M. Myerson (ed) Vol (1):73-83, W B Saunders, Philadelphia, 1996.

9. Goosens M, DeStoop N. Lisfranc fracture dislocations: etiology, radiology, and results of treatment. Clin. Orthop., 176:154-162, 1983.

10. Granberry W, Lipscomb P. Dislocation of the tarsometatarsal joints. Surg. Gynecol. Obstet. 114:467-469, 1962.

Additional References:

Kitaoka H, Alexander I, Adelaari R, Nunley J, Myerson M, Sanders M. Clinical rating system for the ankle-hindfoot, midfoot. hallux, and lesser toes. Foot Ankle 15 (7):349-353, 1994.

McClain E, Gruen G, Hansen S. Fracture dislocation of the tarsometatarsal joint: open reduction and internal fixation with screw fixation. pp 35-44 in Perspective in Orthopedic Surgery. JR Heckman(ed) Vol. 2(1), 1991.

Figure Legends

Fig. 1 Patient with comminuted, intra-articular 1st cuneiform fracture, and diastasis.

Fig. 2A & B Same patient post-op fusion and reduction of diastasis. (Staple is fixating 1st cuneiform, note bone graft).

Fig.3 Technician bone scan of patient who sustained Lisfranc’s fracture and dislocation five months previously who had conservative treatment and continued pain. Note positive uptake especially in first and second tarso-metatarsal articulations.

Fig. 4A & B Same patient post-op fusion and diastasis reduction.

Fig. 5 "Arthrogram" indicating diastasis on a patient that had delayed diagnosis of grade III sprain. Patient underwent ORIF 1 year post-injury and had continued symptoms. Subsequent bone scan showed intense uptake in medial Lisfranc’s and naviculocuneiform articulations.

Fig 6A&B Same patient from Figure 5 who underwent partial Lisfranc’s and midfoot fusion due to continued pain. Tomogram indicates incomplete naviculocuneiform fusion.

Fig. 7 Technicium bone scan of patient that had continued pain from 3rd and 4th tarsometatarso dislocation. Post-traumatic symptoms currently relieved by orthoses.

Fig. 8A&B X-rays of patient with post-traumatic pain in 2nd tarsometatarso joint. (Note narrowing and sclerosis of joint.)

Fig. 9 MRI of same patient (Note effusion of same joint).

APPENDIX Legend:

Dx/Tx = Diagnosis/Treatment

AOFAS = American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society

prev. = previous

Frx/Dis = Fracture/Dislocation

Patients With Trauma to Lisfranc’s Joint

| Patient | Age/Sex | Diagnosis | Time until Dx/Tx | Treatment | Return to (Activity) |

| MB | 10/M | Grade I Sprain | 2 months | Arch Pad | 4 wks (soccer) |

| NC | 41/F | Grade II Sprain | 1 month | Ankle Brace, Arch Pad | 6 mos. |

| BD | 53/F | Grade III Sprain | 2-5 months | Cast Boot | 6 mos. |

| AE | 15/F | Grade III Sprain | 2 days | Cast Boot | 2-5 months (track/soccer) |

| DE | 29/F | Grade II Sprain | 3 months | Arch support | 4 months |

| JE | 23/F | Grade II Sprain | 2 weeks | Cast Boot | 6 weeks (volleyball) |

| II | 30/F | Grade II Sprain | 4 weeks | Cast Splint | 3 months |

| DJ | 31/M | Grade III Sprain | 1 day | Cast Boot | 3 months (running) |

| JK | 54/M | Grade I Sprain | 2-5 months | Arch Support | 5.5 months (dancing) |

| MK | 29/M | Grade III Sprain | 10 weeks | Cast Boot, ORIF Navicular Fracture | 3 months post-op (soccer) |

| MO | 30/M | Grade I Sprain | 2 months | Arch Support | 3 months (dancing, martial arts) |

| Patient | Age/Sex | Diagnosis | Time until Dx/Tx | Treatment | Return to (Activity) |

| ER | 34/M | Grade II Sprain | 1 year | Orthotic | 1 mo. better w/ orthotic (soccer) |

| TS | 16/M | Grade II Sprain | 10 days | Cast Boot/Orthotic | 6 weeks (basketball) |

| DC | 27/F | Grade II Sprain | 3 months | Arch Pad | 1 month (running) |

| CT | 36/F | Grade III Sprain | 12 days | Cast Boot/Orthoses | 4 months (tennis) |

| KV | 20/F | Grade II Sprain | 2 years | ORIF | 6 months (soccer, track) |

| JM | 18/M | Grade I Sprain | 3 months | Arch Support | 6 weeks (football, baseball) |

| NW | 12/F | Grade I Sprain | 3 months | Arch Support/Orthoses | 1 month (ballet) |

| TB | 31/F | Frx/Dislocation | 48 hours | Cast Boot/Orthoses | 6 months (water skiing) |

| LH | 35/M | Frx/Dislocation | 4 weeks | Cast Boot/Orthoses | 6 months (running) |

| AH | 24/F | Frx/Dislocation | 72 hours | Cast Boot/Arch Support | 2 mos. (snowboarding, running) |

| DS | 40/F | Frx/Dislocation | 2 months | Cast Boot/Orthoses | 5 months (martial arts) |

| BE | 51/F | PTDJD | ? | Orthoses | 1 month (hiking) |

| EL | 59/F | PTDJD (prev. sprain) | 5 months | Arch Support | (hiking) |

| JL | 36 | PTDJD | months | Arch Support | Decreased (running) |

| NM | 56/M | PTDJD (prev. sprain) | years | Orthoses | Fusion scheduled (tennis, aerobic) |

| Patient | Age/Sex | Diagnosis | Time until Dx/Tx | Treatment | Return to (Activity) |

| NM | 56/M | PTDJD (prev. sprain) |

years | Orthoses | Fusion scheduled (tennis, aerobic) |

| LR | 56/F | PTDJD (prev. sprain) |

years | Orthoses | (hiking) |

| AS | 60/F | PTDJD (prev. sprain) |

years | Orthoses | Decreased (running) |

| PT | 63/F | PTDJD (prev. Frx/Dis) |

years | Orthoses | Decreased (hiking, tennis) |

| JW | 61/F | PTDJD (prev. Frx/Dis) |

years | Orthoses | Decreased (hiking) |

| IW | 56/F | PTDJD (prev. Frx/Dis) |

2 days Initial fracture dislocation | Frx/Dis treatment w cast Orthoses |

Decreased (tennis) Acquired flat foot deformity |

| JL | 63/F | PTDJD

(prev. sprain) |

months | Orthoses | Decreased (possible fusion) |

| SC | 57/F | PTDJD

(prev. sprain) |

years | Orthoses, NSAIDs | Decreased (tennis, dancing) |

| SC | 57/M | Fusion

(prev Frx/Dis) |

5 months | Fusion 1-5 | 6 months (hiking) AOFAS Score: 92 |

| PM | 61/F | Fusion

(prev Frx/Dis w/BK cast) |

10 days | Prev BE lest, fusion 1&2 | 6 months (hiking, biking) AOFAS Score: 100 |

| Patient | Age/Sex | Diagnosis | Time until Dx/Tx | Treatment | Return to (Activity) |

| CG | 59/F | Fusion (prev. Frx/Dis) | 5 days | Fusion 1 | 6 months AOFAS Score: 100 |

| JG | 39/M | Fusion (prev. Frx/Dis no prior Tx) | 3 mos | Prev ORIF, fusion 1&2 | Additional fusion? AOFAS Score: 65 |

| PH | 63/F | Fusion (prev. sprain)/td> | years | Fusion 1 and cunei | 6 months (tennis) AOFAS Score: 98 |

| AN | 31/F | Fusion (prev. sprain) | 1 year | Prev ORIF, fusion 1&2, Navicular | Additional fusion AOFAS Score: 65 |

Acknowledgments: The author wishes to thank transcriptionist, Julie Clark, for the preparation of this manuscript, and fourth year DPM student Ritchie Steed (CCPM) for his work on data accumulation.

Home | About Dr. Saxena | Articles | Appointments | Shoe List | Orthoses

Medial Distal Tibial Syndrome (Shin Splints) | Sever's Disease/Calcaneal Apophysitis

Ankle Sprains & Calf Strains | Injury Prevention | Heel Pain | Achilles Heel | Ankle Stretching, Rehabilitation & Taping

Return to Sports After Injury | Cycling | Marathons | Videos | Recommended Books | Links

Friends & Patients | Legal Notice | Privacy Statement | Site Map

Copyright © Amol Saxena, DPM - Sports Medicine & Surgery of the Foot & Ankle

Web Site Design, Hosting & Maintenance By Catalyst Marketing Innovations, LLC/ Worry Free Websites